Where is Sarwari No.1 of 1994?

There is a gem of a case on Islamic probate law. It was decided in 1994. For some reason it has not been reported. It is a great mystery. This is the story of that case A Muslim man, Ainuddin, died in 1944. As a Muslim he did not leave a will. He had sons […]

There is a gem of a case on Islamic probate law. It was decided in 1994. For some reason it has not been reported. It is a great mystery.

This is the story of that case

A Muslim man, Ainuddin, died in 1944. As a Muslim he did not leave a will. He had sons and a daughter. Under pre-Independence law, Ainuddin’s residual property passed to his biological children, but in fixed proportions. Today that proposition would have been determined by a Faraid Certificate. Whether then or now, the beneficiaries of a Muslim person’s estate have to go to the High Court. They have to first obtain Letters of Administration. What remains of the estate has then to be divided, under Islamic law, among the deceased’s beneficiaries, in fixed proportions: the Faraid proportions. Under the Syariah system, sons get twice as much as the daughter.

However, recall that Ainuddin died shortly after the Second World War. The Syariah courts had not been been established. The Faraid system was not in place at that time. So any property was then divided between the beneficiaries under common law principles of distribution. That was controlled by a Distribution Act (then called an Ordinance). Biological children to a portion, equally divided among all of them.

Four years after his Ainuddin’s passing, Abdul Aziz, one of the sons, (here the the defendant), took out Letters of Administration. That was in 1948.

In 1949 Abdul Aziz, as the administrator, obtained an oddly worded distribution order.

It was oddly worded because he did not inform the court he had a sister who was also a beneficiary. It was Sarwari, the plaintiff. Her name appeared nowhere in the estate papers or the subsequent orders.

Citing the distribution order as justification, Abdul Aziz, as administrator, distributed the entire estate between himself and his brothers.

Almost half a century later, in 1991, Sarwari, who had by now discovered that she had been cut off from her inheritance, sued the administrator for her portion. The High Court allowed Sarwari’s claim. The court valued Sarwari’s inheritance at RM547,847.21. It was a huge sum. And subsequent interest ballooned it to an ever higher figure.

The Sarwari case deals with the question of what common law relief can be obtained for a breach of trust on an Islamic estate. Where an administrator of an Islamic estate had deprived a beneficiary out of her inheritance, the question was whether she was entitled to recover all losses suffered from the administrator alone. Or was she also required to pursue other beneficiaries to whom her portion of the inheritance had been wrongfully distributed.

Sarwari v Abdul Aziz [No.1] [1994] answers that question.

The law discussed in these cases is complex and rather deep. These legal principles are more relevant today than they were in 1994.

Other caselaw do not adequately deal with this question. It seems that that a series of three ‘Sarwari’ cases have completely dealt with this legal issue: Sarwari v Abdul Aziz [No.1], [No.2] and [No.3].

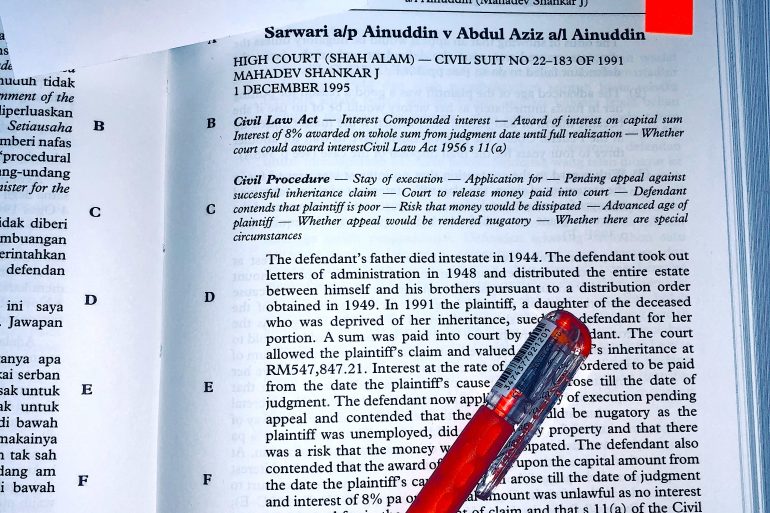

Nos, [2] and [3] are reported: [2000] 5 MLJ 391 (or the CLJ version is [1999] 8 CLJ 534), and [2001] 6 MLJ 737.

But Sarwari v Abdul Aziz [No.1] has disappeared from the face of the earth. It is missing!

So, I gathered the text of the judgement of that case from counsel, and sent it off to the law journals. I asked that it be published. The judgement was published on 27thOctober 1994 at the Shah Alam High Court. A judge who is well known for his juristic brilliance wrote it. His name is Dato Mahadev Shankar J (as he then was). Later he became a Court of Appeal judge. He is still around.

The counsel who argued these three cases to their conclusion—and ultimate success—was Mr T. Gunaseelan.

I think it would be a good idea to publish the case. Well?