How did a Scottish snail and an Irish-Welsh judge protect you against carelessness?

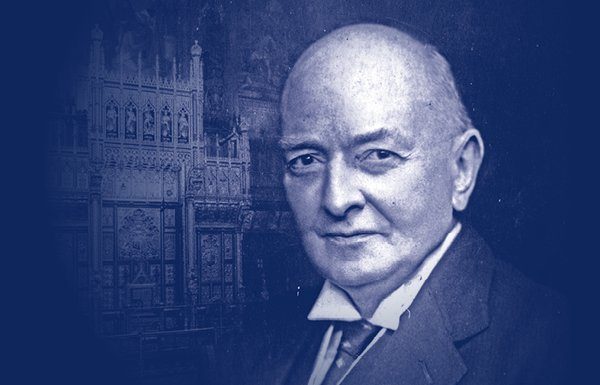

There are many rights you enjoy today. You do not even think about them. But for a British judge and a Scottish snail, you may have lost it all. Should you not celebrate Lord Atkin?

If someone crashes into your car, if a doctor gives you negligent treatment, or if an engineer gives you bad advice – how are you to be protected?

You can sue them, and demand compensation.

Where did you get that right?

That came from the death of a Scottish snail, and Lord Atkin, an Irish-Welsh judge.

These stories tell you what happened.

Ginger beer is good with ice cream

On 26 August 1928, Mrs. Donoghue’s lady friend bought her some ice-cream. This was at a café in Paisley, Scotland.1Lord Atkin, Geoffrey Lewis, Butterworths, 1983

Her friend suggested that some ginger beer would make their repast better. So she bought a bottle of ginger beer for Donoghue. The retailer supplied it in a sealed, dark, opaque glass bottle.

Donoghue had the first sip. They conversed.

Her friend topped up her tumbler.

Up floated the remains of a decomposed snail.

Donoghue became violently ill.

She sued the manufacturer.

Donoghue’s gamble

The manufacturer relied on an old law.

He said that since Donoghue had had no contract with the manufacturer, she could not sue him.2Winterbottom v. Wright 10M. & W. 109; Blacker v. Lake & Elliot, Ltd (1912) 106 L. T. 533; George v. Skivington L. R. 5 Ex. 1

In fact, Donoghue had not even paid for the ginger beer: her friend had.

It looked like she had no hope.3In an earlier decision, a Scottish court had dismissed, and refused to order any compensation, to a person who had drunk a similar bottle of ginger beer, but which had contained not a snail, but a dead mouse: Mullen v. AG Barr [1929SC 461

Was there a broader principle at play?

Donoghue argued that there was a broader principle: every manufacturer owed a duty to anyone who used his article – even though there was no contract between them. They laughed her to scorn.

Eventually, the question came up before the House of Lords, where Lord Atkin was a judge.

‘Hard cases make bad law’

It was a US judge, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who said that.4Northern Securities Co. v. United Slates 193 LIS 197 (1904) 24 S. Ct.431

It stands to reason. If you look at some old cases, you will see how judges developed the law on carelessness, and how bad the situation was for the man on the street.5Winterbottom v Wright (1842) 10 M & W 109.

An injured wagon driver cannot sue

In the nineteenth century, they did not have emails.

Mail coaches sent out letters. These were horse-drawn wagons.

In 1842, the Postmaster-General contracted with one Wright to maintain the safety of these coaches.

While Winterbottom was driving it, a coach collapsed, injuring him.

Winterbottom sued Wright, complaining Wright had been negligent.

The court threw it out because Wright did not owe any duty to Winterbottom, a third party to the contract.

You cannot sue a careless surveyor

In 1893 a mortgagee loaned money to house owners to build two homes.6Le Lievre and Dennes v. Gould [1893] 1 QB 491 The lender agreed to release the money in instalments, at specified stages.

A surveyor issued some certificates, which confirmed that some stages of the construction were completed.

On the faith of those certificates, the lender released the loans.

The surveyor had no contract with the lender.

The certificates contained untrue statements – but the surveyor was not dishonest. The lender suffered losses. He sued the surveyor.

The Court of Appeal threw out the case. It ruled that unless the lender could show the surveyor had deceived him, the lender could not sue him.

The judge, Lord Esher, said something quite alarming:

‘What duty is there when there is no relation between the parties by contract? A man is entitled to be as negligent as he pleases towards the whole world if he owes no duty to them.’

Does ‘near another man’ sound familiar?

Despite that, Lord Esher said something else too.

Lord Esher observed that in some situations, a man may owe a duty to another, even though there is no contract between them.

If a man is near another man, or his property, it is the duty of the first not to do anything injurious to that man or his property. 7Ibid, at p. 497

Note the word ‘near.’

Ask yourself if it has to do anything with the word ‘neighbour’.

It is a concept that Lord Atkin would develop later.

A lamp explodes on a wife

In 1851, a man sold a defective lamp.8Longmeid v. Holliday Ex., 76, 768 It exploded. The buyer’s wife was injured.

The seller was not the manufacturer. He had no idea the lamp had been defective.

The court threw out the case.9 The judge there was Parke B, who said: “[It] would be going much too far to say, that so much care is required in the ordinary intercourse of life between one Individual and another, that, if a machine not in its nature dangerous, …but which might become so by a latent defect entirely unknown, although discoverable by the exercise of’ ordinary care, should be lent or given by one person, even by the person who manufactured it, to another, the former should be answerable to the latter for a subsequent damage accruing by the use of it.

Exceptions to mitigate the harshness of the law

In mid-nineteenth century, British judges were becoming increasingly worried that the law was being too hard on the poor and unsuspecting citizens.

They tried to mitigate its harshness by creating several exceptions.

Two are notable: if an article was, in itself, dangerous, and it caused harm, the seller was liable, contract or no.

Second, if a seller sold an article which he knew was bad, then he had no excuse – the law would not protect him.

The following cases demonstrate these exceptions.

A gun that took off a hand

In 1835, Levy, a gunsmith, sold a gun to Langridge. Langridge said he and his sons would use it for recreational shooting. Levy assured Langridge that the gun was safe.

When his youngest son used it to shoot some birds, it exploded.

His hand was so badly mangled, it had to be amputated.

When sued, Levy raised the same point – the son had no contract with him.

The court ruled that if an article was in itself dangerous, a person who sold it was liable – a contract was unnecessary.10Langridge v. Levy, [1835-42] All ER Rep. 586 at p. 590, 591; 2 M. & W. 519; 4 M. & W 337

A bad shampoo for the wife

In 1869, Skivington, a chemist, sold some shampoo to Joseph George.

Skivington assured Joseph that he had compounded it skillfully and carefully, using chemical ingredients known only to himself. He also assured the shampoo was safe.

George’s wife, Emma, used it and suffered damage. She had no contract with Skivington.

When sued, Skivington protested that Emma was a stranger to him. Unless he had known the shampoo had been defective, he was not liable.

Skivington said he had no idea the shampoo was unsafe.

The court ruled that if Skivington knew that Emma would use it, and that was quite enough to fix him with liability.11Pigott B, at p.4

In Donoghue’s case, Lord Buckmaster would express his dislike for this principle.

A painter’s plank, hoisted by a bad rope

Then came an unusual case.

It did not fall into the exceptional cases. It concerned a painter.

In 1883, a ship had berthed at a dock.12Heaven v. Pender, trading as West India Graving Dock Company [1883] vol X1, p.503 Pender owned the dock. He put up a platform outside the ship.13Called a’stage’ It was a plank suspended by a rope.

Heaven, a painter, had to use Pender’s platform to paint the ship. The rope broke. Heaven fell and was injured.

But Heaven had no contract with the dock owner.

Heaven sued him anyway.

The judges directly linked the dock owner to the work Heaven had performed. Pender had a duty to Heaven. He had to take care that the platform and the rope were in a fit state.

Lord Buckmaster would attack this case too.

Was Donoghue’s case, lost?

When Donoghue’s question came up before the House of Lords, she had to bring herself within the recognised categories.

Otherwise, her case was lost.14WVH Rodgers, Winfield and Jolowitz on Tort. 17th edition, Thomson Sweet and Maxwell, p.52

Lord Buckmaster’s fierce dissent to Atkin

Buckmaster was a brilliant, old school judge.

He thought Donoghue had no right to sue the manufacturer.

He dissented, putting up a big fight. 15See Donoghue, p.568, and at p.576.

Buckmaster’s fear of ‘limitless mischief’

Buckmaster feared that a broad principle – such as the one Donoghue advanced – would invite ‘limitless mischief.’16Ibid, Lewis, at p.56

It is for this reason that Buckmaster quotes a line from the wagon driver’s case:17Supra, Winterbottom v. Wright.

‘If we go one step beyond that, there is no reason why we should not go fifty.’18See Donoghue, p.568

Buckmaster’s wish ‘to bury the perturbed spirits’ of the Exceptions

Buckmaster poured scorn over the ‘exceptional cases’ – ship painter’s case19 Heaven v. Pender and the shampoo case – 20George v. Skivington with this withering remark:

‘I do not propose to follow the fortunes of George v. Skivington: few cases can have lived so dangerously, and lived so long.’21Ibid, p.570

Mocking these judgements, he remarked,

‘it is, in my opinion, better that they should be buried so securely, that their perturbed spirits shall no longer vex the law’.22Ibid, at p.576

It is but ‘a plank in a shipwreck’

Buckmaster contemptuously dismissed Atkin’s attempts to extract any general principle from the old cases. He discounted it as,

‘a tabula in naufragio for many litigants struggling in the seas of adverse authority.’23He was criticizing Sir William Brett, Master of the Rolls who sought a general principle in the Heaven v Pender case

The Latin phrase meant ‘a plank in a shipwreck.’24See p.573, recalled by Geoffrey Lewis, ‘Lord Atkin’ 1983 ed. at p.56

Buckmaster meant that Lord Esher’s search in the painter’s case, and Atkin’s forage for a universal principle were as useless as floating debris.

Buckmaster’s ‘passionate sarcasm’, says Heuston, had arisen because Buckmaster thought Atkin, along with the majority, had jumped over the side.

Heuston says it was well ‘beyond the permissible limits of judicial law-making.25‘The Life of Lord Chancellors’ 1864 ed., at p.309. Heuston would note cryptically that Time has vindicated the majority rather than Buckmaster.’

Lord Atkin begins

Atkin explained how difficult Donoghue’s problem was. He said,

‘I do not think a more important problem has occupied your Lordships in your judicial capacity: important … because of its bearing on public health….’ 26p.57926

Atkin surveys old law — and sees no unifying principle

When he surveyed the law, Atkin found no unifying statement of principle about carelessness.27Ibid, Lewis, p.561

He thought the law was not in touch with society or its everyday needs.28Ibid, Lewis, p.57.

How had the US judges dealt with it? By problem with a wooden wheel

As early as 1916, a brilliant American judge, Benjamin Cardozo J, had already recognised the existence of a ‘general principle’ in a similar situation.

One MacPherson bought a car from a retailer in New York. Buick Motor had manufactured it.

One of its wooden wheels, made from defective material, collapsed. MacPherson was injured.

When MacPherson sued Buick Motors, he was rebuffed by Buick’s defence that he had had no contract with Buick.

Benjamin Cardozo J sank Buick’s defence.29See Cardozo J in Donald C. MacPherson v. Buick Motor Company 217 N.Y. 382 at 385

Cardozo J said the question to be asked was not if Buick had concealed the defect, but whether it had ‘owed a duty of care and vigilance to anyone but the immediate purchaser.’

Atkin’s analysis

Compared to Buckmaster’s impenetrable wall of opposition, Atkin’s analysis of the law was deliberate, meticulous, refined, and expressed in arresting language.

He analysed no less than 25 old cases and scrutinised their very foundational philosophy.

A study of his judgement is like looking at an expensive carpet with a weave of different colours, all brought into harmony with a clear pattern.

Atkin describes the scene…

Atkin was a master of the art of restatement: he took a difficult problem and reduced it into a simple story. He then drew out a legal principle. See how he does it:-

‘The manufacturer puts up an article of food in a container which he knows will be opened by the actual consumer.

There can be no inspection by any purchaser and no reasonable preliminary inspection by the consumer.

Negligently, in the course of preparation, he allows the contents to be mixed with poison.’

He poses the dilemma…

‘It is said that the law of England and Scotland is that the poisoned consumer has no remedy against the negligent manufacturer.’

And explains what is wrong…

Then he sets the scene for what he is about to say:

‘If this were the result of the authorities, I should consider the result a grave defect in the law, and so contrary to principle that I should hesitate long before following any decision to that effect which had not the authority of this House.’

Atkin discarded ‘the debris of old cases’ so that these should not stand in the way of new developments in the law, to accord with ‘both common sense and social needs.’30Ibid, Lewis, p.62

Lord Atkin’s General Principle

Atkin formulated this principle:

If you foresee that your actions would directly injure another person, if you so acted,31The law states that not only ‘actions’ but also ‘omissions’ are relevant. By ‘omission’ is meant a failure to act when the law requires one to act in a certain way and gave injury, you would be liable for it.32’The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law, ‘You must not injure your neighbour’; and the lawyer’s question, ‘Who is my neighbour?’ receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who, then, in law is my neighbour? The answer seems to be – persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.’ Where did Atkin get this ‘neighbourhood’ idea? Geoffrey Lewis (ibid)) says that months earlier, in October 1931 Atkin gave a lecture, where he said something profound. Atkin said, ‘The British law has always necessarily ingrained in it moral teaching in the sense: that it lays down standards of honesty and plain dealing between man and man. The idea of law is that the obligations of a man are to keep its word. … He is not to injure his neighbour by acts of negligence; and that certainly covers a very large field of the law. I doubt whether the whole of the law of tort could not be comprised in the golden maxim to do unto your neighbour as you would that he should do unto you’. [Law is an educational subject, 1932, Journal of the South of Public Teachers of Law] [I paraphrase].33On 27 June 1944, Viscount Simon, paying tribute to Atkin’s memory at the House of Lords said, ‘[Atkin’s] strength largely consisted in this connection that English law is at bottom a sensible thing, and that, when it grasped the facts and applied with great knowledge of the law to those facts, the conclusion would emerge.’

A silent, passing leviathan…

The case created a legal revolution.34Ibid, Lewis, p.62. It was in 1963 that Lord Devlin spoke of it in the Hadley Byrne case Yet, like a leviathan passing silently below a ship’s belly, Donoghue passed over the UK,35Ibid, Lewis, p.67 and remained unremarked.36 Indeed, the Commonwealth showed greater receptivity and understanding of Donoghue case than British lawyers. FC Underhay, wrote: ‘Lord Atkin’s judgment is at once stamped as perhaps the most impressive and certainly the most authoritative effort ever made to generalise the English law of negligence’, and extolled the ‘neighbour principle’ as, ‘a guide to judges were before there was none.’(10C and BAR are a pre-615.

It was only because of Donoghue that there was a massive development in the law of negligence.

But for a time, the courts did not seek to develop a general principle, as Atkin desired. They expanded in piecemeal basis.

Thirty-two years later the UK courts decided that negligence could be committed both by words and by deeds.37 Hedley Byme v. Heller (1964) AC 465. That was not helpful.

It would get worse…

In 1977, in the Anns case, the House of Lords took what Lord Atkin said farther than what he had intended.38Anns v Merton London Borough Council, [1978] AC 728; [1977] UKHL 4. They ruled that there a duty of care ‘was established’ and that harm was foreseeable ‘unless’ there was good reason to judge otherwise.39Kirsty Horsey & Erica Rackley , Tort Law (4th ed., OUP Oxford 2015)60]

This was all very confusing.

Correcting the wayward ship

In 1990, in a case called Caparo Industries plc v Dickman, the House of Lords had to correct the wayward ship.40Caparo Industries plc v Dickman [1990] UKHL 2 Lord bridge used Cardozo J himself as a crowbar to displace what was decided in Ann’s case.41Cardozo J said in 1931 that one could not create a risk of ‘liability in an indeterminate amount for an indeterminate time to an indeterminate class.’

What is it now?

Caparo – which is the current law – decided that a court must ask itself three questions:42Lord Neuberger said, ‘The House of Lords in Caparo identified a three-part test which has to be satisfied if a negligence claim is to succeed, namely (a) damage must be reasonably foreseeable as a result of the defendant’s conduct. (b) the parties must be in a relationship of proximity or neighbourhood, and (c) it must be fair, just and reasonable to impose liability on the Defendant. [’Reflections on the ICLR Top Fifteen Cases: A talk to commemorate the ICLR’s 150th Anniversary Lord Neuberger, 6 October 201]5. Caparo starts from the assumption no duty is owed until the three stage test is satisfied. The criteria are: (1) Foreseeability, (2) Proximity and (3) whether it is fair, just and reasonable to impose such a duty: [ibid, at p.66]

(1) Because of what the defendant did, was the (victim’s) damages reasonably foreseeable?

(2) If Yes, were the parties, to be considered, in law, ‘neighbours’ as such?

(3) If Yes, is it fair to make the defendant liable?

Can you see how the law moved, while you were not looking?

Even if you are not a lawyer, you will see straight away that what Caparo laid down departs from the law in Donoghue v Stevenson: it is certainly different from what Wilberforce said in the Anns case.

As a child takes stumbling steps to walk, this is how the law develops.

But for Atkin, that would not have happened.

The Challenger Deep

The case of Donoghue is a reflection of Atkin himself: self-effacing, but possessed of a scholarship as deep as the Mariana Trench – the deepest part of the ocean.

This is why Atkin is so revered.

Did Lord Atkin deserve top marks?

In 2015, Lord Neuberger cited 15 cases as being the very best in the last 150 years. One was Donoghue.

Neuberger also gave ‘credits’ for the judges’ performance.

In 150 years, only two judges had top marks: three credits, the maximum.

Atkin was the first to be celebrated.43 ‘Reflections on the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting Top Fifteen Cases: A talk to commemorate the ICLR’s 150th Anniversary Lord Neuberger, 6 October 2015, paragraph 16.

(Lord Walker was the other, but that is a story for another day…)

[The author expresses his gratitude to Ms. KN Geetha, Mr. JD Prabhkirat Singh, Mr. GS Saran, Miss KP Kasturi, Mr Ganavathi Naidu, Mr. T. Gunaseelan and Ms. Amuthambigai Tharmarajah for their assistance.]