Who is the Chief Minister of Sabah?

Sabahans are troubled by this question. Is that the only question?

Was Musa Aman lawfully removed as the Chief Minister of Sabah? That is the question that troubles everyone in Sabah. That is only half the problem.

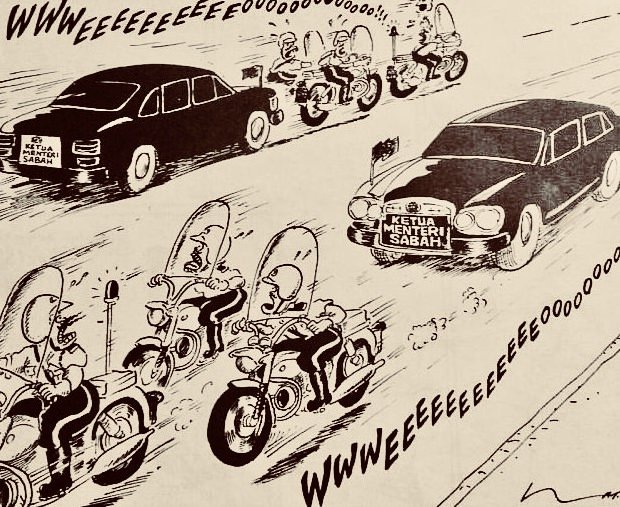

In 1986 the artist Lat drew a cartoon. It showed two luxury cars, travelling in opposite directions. Wailing police escorts precede them. Klaxon horns tear into the silence of the countryside. On each car is a number plate emblazoned with the words, ‘Chief Minister, Sabah.’ Bewildered policemen escorting one one car stare at the identical, opposing car. That graphic dispute eventually resolved itself into a suit: Abdul Ghapor Haji Salleh v. Tuan Yang di-Pertua Negeri [1988].

In that case, the Governor had dissolved the Sabah Legislative Assembly. That was because the Chief Minister had lost command of the State Assembly. The plaintiff, Abdul Ghapor, alleged that the Governor had acted outside the Constitution. He sought various injunctions. The court declined to grant the orders. The Governor’s conduct, the judge said, had been entirely consistent with the Constitution.

Fast forward 23 years: go to Perak.

The Perak Fiasco

By the time the 12th General Election had been concluded on 8 March 2008, opposition parties had wrested the Perak state off the hands of Barisan Nasional. The opposition won 31 out of the 59 Legislative Assembly seats. With a wafer-thin majority of three seats, Nizar formed the state government and became its Chief Minister.

This was in the days when members of political parties pre-signed a letter of resignation.

If any rogue assemblyman decided to go amphibian, and ‘leap over’ to the ‘other’ side, the letters would be handed in to the Speaker. The seat would fall vacant.

At least, that was the plan.

It did not work.

Nizar was appointed as the Menteri Besar on 17 March 2008. Trouble began to brew.

In early 2009, the Speaker of the State Assembly announced that three assembly members had ‘resigned’. He said he had ‘accepted’ their resignations. He declared their seats vacant.

The trio denied these statements.

The Election Commission refused to accept that there was any ‘casual vacancy’ for the three state seats. The trio then wrote to the Sultan.

They said they had ‘lost confidence in Nizar as the Menteri Besar’ but wished ‘to maintain’ their positions as members of the Legislative Assembly.

And, unsurprisingly, they declared their support for BN.

Chief Minister Nizar, by then in a sea of trouble, asked the Sultan to dissolve the Assembly.

He was quite entitled to do so.

The Constitution seemed to be on his side: [Art 16(6), Perak Constitution].

The constitutional provisions of the State of Perak relating to the Assembly’s dissolution, and the constitutional powers of the Sultan, mirror, rather nicely, the corresponding articles in the Sabah Constitution.

Meanwhile, BN claimed that it had command of 31, and therefore a majority, of the members of the Assembly. It asked that Dr. Zambry be appointed as MB.

The Sultan did something unusual.

His Majesty interviewed the 31 members of the Legislative Assembly.

That had never been done before.

After these interviews, the Sultan refused to dissolve the Assembly.

His Majesty asked Nizar and his Executive Council to resign.

Now, like most state constitutions, the Perak State Constitution treats a Chief Minister differently from members of the Executive Council. Council members have no security of tenure.

Under the Perak Constitution, every member of the State Executive Council – other than the Chief Minister – holds his office ‘at the pleasure’ of the Ruler [Art. 16(7)].

There is an identical provision in Sabah [Art. 7(3)].

This is known as the ‘Doctrine of Pleasure’: durante bene placito regis – ‘No one may hold an official position against his ( King’s) will’.

The Perak Sultan then appointed Dr. Zambry as the Menteri Besar.

Unhappy with the Ruler’s decision, Nizar filed for a judicial review.

He argued that he, as the Chief Minister – unlike other members of the Executive Council – did not hold office as CM ‘at the pleasure’ of the Sultan.

He said the operative moment that bound the Head of State was the first day Nizar had presented the Ruler with evidence that he enjoyed the confidence of the Assembly’s majority.

So, there was only one way the MB could have been dismissed, Nizar argued.

The Legislative Assembly had to meet and carry a vote of no confidence against him. To support what he said, he pointed to a Sarawak case.

It was decided by the Federal Court – Stephen Kalong Ningkan v. Tun Abang Haji Openg & Tawi Sli [1966].

That case had followed a Nigerian case called Adegbenro v. Akintola [1963].

In the Adegbenro case, the court had decided that a Head of State could not dismiss a Chief Minister.

A second process had to be initiated.

It was for the State Assembly to decide whether the incumbent Chief Minister enjoyed the Assembly’s confidence.

That was the matter for the Assembly, not the Governor.

The High Court judge felt bound by the 1966 Sarawak case.

He ruled that the Perak Ruler had no power to dismiss Nizar as MB. He ruled that if Nizar had lost the Assembly’s confidence, only the Assembly could determine the issue – that too by a vote of no confidence carried out within the Assembly.

The Sultan, the judge ruled, was not entitled to interview the members of the Assembly to ascertain who commanded the confidence of the Assembly.

This time it was Dr. Zambry, the BN nominee, who appealed against the High Court’s decision. The Court of Appeal agreed with Dr Zambry. It reversed the High Court.

The Court of Appeal, in turn, ruled that the Sultan had ‘an absolute discretion’ whether he wished to dissolve the Legislative Assembly.

It held that Nizar’s refusal to tender his resignation was not only ‘a breach of convention,’ but was also ‘undemocratic’.

The Court of appeal ruled that Nizar’s acts had contravened the state Constitution.

It held that when Nizar refused to tender his resignation, his position as MB had fallen vacant.

When that happened, ruled the Court of Appeal, instead of calling for the Assembly’s dissolution, the Ruler could act on his own volition.

He could dismiss the Menteri Besar.

Nizar filed a final appeal to the Federal Court. It dismissed Nizar’s appeal.

The Federal Court upheld its previous decision in a 1995 case called Datuk Amir Kahar Tun Datu Haji Mustapha v. Tun Mohd Said Keruak & Ors.

There, following an exodus of PBS members to BN, Pairin Kitingan tendered his resignation. The main issue in the Amir Kahar case was whether Pairin’s resignation had been constitutionally valid, and if so, whether that led to the total resignation of his whole Cabinet.

The Federal Court answered ‘Yes’ to both questions. It ruled that when Nizar had lost his majority in the State Assembly, it was mandatory for him to resign his post as Menteri Besar. Any refusal to resign, the court said, brought about the Chief Minister’s ‘deemed’ dismissal in law.

Now fast forward to 2018.

So what happened in Sabah?

On 9 May 2018, the 14th general election was concluded across the nation.

The state of Sabah has 60 state assembly seats.

On 10 May Musa Aman claimed that he had formed a coalition government of 31 assemblymen from two parties: BN and STAR.

On the same day, he asked the Governor of Sabah to appoint him as the Chief Minister.

The Governor complied. Like its twin in the Perak Constitution, Article 6(3) of the Sabah Constitution states that:-

‘… the Yang di-Pertua Negeri shall appoint as Chief Minister member of the Legislative Assembly who in his judgement is likely to command the confidence of the majority of the members of the Assembly …’

The Sabah Constitution – like the Perak Constitution – also states that: –

‘… if the Chief Minister ceases to command the confidence of the majority of the members of the Legislative Assembly the Chief Minister shall tender the resignation of the members of the Cabinet.’ [Article 7(1)].

Like Perak, Sabah seems to have had its share of leaping assemblymen.

On 11 May 2018, six BN state assemblyman defected to Warisan.

It is a party headed by Shafie Apdal.

That gave Shafie Apdal command of 35 Assemblymen’s support in the state Assembly.

It was Shafie Apdal’s turn to besiege the Governor’s gates.

On the evening of 13 May 2018, the Governor, Tun Johar Mahiruddin, requested that Musa Aman step down from the post of Chief Minister.

Musa declined the invitation.

On 13 May 2018, the Governor notified Musa Aman in writing that ‘effective 12 May 2018’, Musa was ‘no longer CM of Sabah.’

Shafie Apdal was then sworn in as Chief Minister.

Immediately after Shafie Apdal had been sworn in, a number of strange things happened.

First, the Governor filed a police report that Musa Aman had ‘intimidated’ him at the Palace.

Second, Musa Aman was last seen on a Malindo flight to Kuala Lumpur. There was news on that he had ‘lawfully’ left Malaysia to the UK ‘for medical and personal reasons’ [16 May].

Strangely, the Director-General of Immigration, Mustafar Ali, reported that ‘there were no records of Musa Aman having left the country’.

A week later, a team of MACC investigators raided Musa Aman’s home [on 23 May 2018].

Then the Royal Malaysian police applied to Interpol to have a ‘Red Notice’ issued for Musa Aman [on 28 June 2018].

The Red Notice was requested on the ground that the Malaysian police were investigating allegations that the ex-CM had ‘intimidated Sabah Governor Johar Mahiruddin’, just before Musa had been sworn in.

There was also the ground that MACC was investigating him on allegations of bribery of certain Sabah assemblymen.

Three months and five days after leaving Malaysia, Musa returned to Malaysia [on 21 August]. He was arrested for criminal intimidation of the Sabah Governor [on 23 August 2018].

He has since been released on police bail.

Some three months and 19 days after he had left Sabah [on 16 May 2018], Musa returned to Kota Kinabalu [on 5 September 2018].

These circumstances raise several questions: –

First, could the Governor dismiss Musa Aman as Chief Minister?

Second, did Musa Aman abdicate his position as Chief Minister?

Third, did Musa Aman breach his Oath of Office?

Fourth: Is Musa’s suit academic?

But there is an over-arching issue that is far more important than these questions. We shall deal with it at the end.

Did the Governor have the constitutional power to dismiss Musa Aman as Chief Minister?

The answer to this question very much depends on the facts and on the proper construction of the Sabah Constitution. The merits of the parties’ respective positions cannot be determined by an article such as this – for the ex-CM has filed an action in court.

But we could examine the law and discuss what it says.

An old English principle states:-

‘He who appoints can dismiss, so long as the dismissal is reasonable in all the circumstances.’

But administrative law lawyers argue that this only applies to employment matters, not to constitutional cases.

Remember the Perak Menteri Besar case in 2009?

That seems to suggest that the position of a Chief Minister who has lost command of the state Legislative Assembly, and who refuses to tender his resignation, is ‘deemed’ – by operation of the law – to have fallen vacant.

That conclusion can only be reached if the court determines that the Constitution of Sabah and the Constitution of Perak are identical on this point.

Then there is the opinion of an Indian constitutional expert, Soli Sorabjee.

Where a state constitution lacks an express provision for the removal of the Chief Minister, he says, one has to fall back upon British conventions.

One such convention is that the Head of State cannot remove the Chief Executive because it ‘subverts the democratic basis of the Constitution:’ [Surajeet Das Gupta, Inderjit Badhwar, India Today, May 15, 1987].

So we need to study a series of Indian cases that commence in the late 1960s. The starting point is the 1967 West Bengal case of Mr Ajoy Mukherjee.

When the State Legislative Assembly was not in session, some of its members withdrew their support from Chief Minister Mukherjee.

The Governor asked the Chief Minister to convene an early session of the State Assembly. He wished to test whether Mr. Mukherjee still enjoyed the confidence of the Assembly.

When the CM betrayed a reluctance to carry out this Damoclean invitation, the Governor dismissed the CM and his Cabinet.

A new ministry headed by Dr P.C. Ghose was sworn in.

But things did not end there. When the Assembly met, the Speaker brazenly adjourned the Assembly.

He ruled that the Governor’s dismissal of Mr Mukherjee had been unconstitutional.

When the dispute reached the Calcutta High Court, the court declared that the Governor’s dismissal of the CM had been constitutional.

The third concerns the case of Mr Abdul Rahman Antulay.

In 1982, he was the Chief Minister of Maharashtra.

There were allegations that he had been involved in corruption.

The Governor removed him as CM [years and years later, he was exonerated of the charges of corruption].

The courts upheld that decision.

Whether the decisions in the Indian cases apply in Sabah would depend on whether the state constitutions of the Indian states of West Bengal and Maharashtra are identical to the Constitution of Sabah.

Let the courts decide that.

Did the Musa Aman abdicate his position as Chief Minister?

That Musa Aman had left the country, legally or otherwise, may, or may not amount to an abandonment of his post.

That is a question that the High Court has to decide.

If the High Court decides that Musa had left the State without the proper authority of the Governor or Federal authorities – which is a matter of proof before the High Court– and if it is so proven – then the question is whether Musa’s absence amounted to an act of abandonment, or dereliction of his responsibilities – amounting to an abdication of his post as CM.

But why stop there: why don’t we ask one more question?

Did Musa breach his Oath of Office?

On his appointment as the CM of Sabah, Musa would have taken a Constitutional oath of office: [See the Constitution of Sabah, Part II, First Schedule].

The oath would likely have been in the following words:-

‘I Tan Sri Musa bin Aman, having been appointed to the office of Chief Minister of the State of Sabah, do solemnly swear that I will faithfully discharge the duties of that office to the best of my ability, that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the State of Sabah and to the Federation of Malaysia, that I will preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the State of Sabah, and that I will not directly or indirectly communicate or reveal to any person any matter which shall be brought under my consideration or shall become known to me as Chief Minister except as may be required for the due discharge of my duties as such or may be specially permitted by the Yang di-Pertua Negeri.’

If that is so, was Musa’s departure from Malaysia, (assuming he took no steps to apply for proper leave, and assuming he did not ensure that someone took charge of the State Government in his stead), was he in dereliction of his duties?

Was all that sufficient to allow the Court to declare him as having abandoned the office of CM?

For that, we have to wait for a judicial ruling.

Is Musa’s suit academic?

Recently the Bar Council, relying on Article 122(1A) of the Constitution, sued the ex-Chief Justice alleging that the ex-Chief Justice’s appointment as an Additional Federal Court Judge had been unconstitutional.

Last week the Federal Court handed down an unusual decision.

It ruled that it would not answer an ‘academic question’.

Currently, does someone else, some person other than Musa Aman, enjoy the confidence of the State Assembly of Sabah?

If so, has Musa’s suit become academic?

Is the fact that there is now a new CM who enjoys the confidence a majority the Legislative Assembly, relevant to the questions now posed to the High Court?

Those are the questions that the High Court has to mull over.

And only the High Court can determine the answers to these questions.

We wait with bated breath.

But really that is not the real problem, is it?

Should party-hopping be banned?

Isn’t that the real issue here?

Election candidates make all sorts of promises to the people.

They guarantee positive changes.

They promise to act in the best interests of the people.

The election comes.

The moment they win the elections, the successful candidates fall prey to the highest bidder.

We all remember how, in 1994, Pairin Kitingan, with the help of Tun Datu Mustapha Harun, had obtained a two-seat majority.

That too after an olympian struggle with Barisan Nasional.

Fearful of defections, he stood before the Governor’s gates for 36 hours.

Eventually, he was allowed entry, and he formed the Government.

And then, weeks later, there was an amphibian migration to BN.

It is not important what Pairin, or PBS, lost.

The underlying question is: why do these things keep recurring, time after time?

Because the people’s representatives do not respect their voters.

In doing this, they sell out their voters, their hopes and aspirations.

They deceive their constituents.

They betray their promises.

They simply do not care.

Elected representatives who forget their promises should not be allowed to represent the people

And so, it is time we bring in a new law – one that declares that once a person jumps party, his or her seat falls vacant.

And all the expenditure of re-election of the jumping candidate shall have to be borne by him.

And he cannot, for ever, stand for any election at any level.

And, thereafter, he cannot accept any public or private position of responsibility.

Surely the people of Malaysia deserve better than amphibians as representatives?

[The author expresses his gratitude to Ms Sucy Ng, a Sabah lawyer]